The European Union and the Sahel: the day after

The European Union and the Sahel: the day after

Policy Analysis 1 / 2025

By Angela Meyer, Loïc Simonet & Johannes Späth

Executive Summary

Geopolitics are changing fast in the Sahel. Over the past three years, the region, one of the most impoverished and imperilled of the world, has undergone a dramatic cycle of regime change and alliance shift, which has significantly challenged the strategy and engagement of the European Union (EU) and its member states in the region. Against the background of this severe crisis in EU-Africa relations and growing anti-Western sentiments, new international players are appearing or increasing their influence, such as the Russian Federation, China and Turkey.

It is now urgent for the EU to acknowledge the new situation in the Sahel region and rethink its approach. If Europe wants to remain engaged in the region, it should forge a new path guided by day-after policies, with a view to rebuilding trust in the EU as a reliable partner. This Policy Analysis draws on the Panel Discussion held at the oiip on 28 November 2024 on the same topic, in cooperation with the Austrian Federal Ministry of Defence (bmlv).

This piece dives into the drivers of the Sahel region’s geopolitical dynamics and critically investigates the shortcomings of the EU’s approach to the region. It concludes with actionable recommendations for recalibrating the EU’s Sahel policy to address past mistakes, prevent further damage, and adapt to the region’s evolving realities.

Zusammenfassung

Die Sahelzone befindet sich in einem raschen geopolitischen Wandel. In den vergangenen drei Jahren hat die Region, die zu den ärmsten und gefährdetsten der Welt gehört, einen dramatischen Zyklus von Regimewechseln und Bündnisverschiebungen erlebt, der das Vorgehen und Engagement der Europäischen Union (EU) und ihrer Mitgliedstaaten in der Region auf eine schwere Probe gestellt hat. Vor dem Hintergrund dieser schweren Krise in den Beziehungen zwischen der EU und Afrika und der zunehmend antiwestlichen Stimmung treten neue internationale Akteure wie Russland, China und die Türkei auf, die ihren Einfluss aufbauen oder verstärken.

Die neue Situation in der Sahelzone erfordert von der EU, ihren Ansatz dringend zu überdenken. Wenn Europa sich weiterhin in der Region engagieren will, muss eine Neuausrichtung stattfinden, die sich an den aktuellen Entwicklungen orientiert und das Vertrauen in die EU als zuverlässigen Partner wiederherstellt. Diese Policy Analyse stützt sich auf eine Paneldiskussion, die am 28. November 2024 am oiip in Zusammenarbeit mit dem österreichischen Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung (bmlv) zum selben Thema stattgefunden hat.

Die Analyse befasst sich mit den Impulsen und Ursachen der geopolitischen Dynamiken in der Sahelzone und untersucht kritisch die Schwächen und Fehleinschätzungen des bisherigen Ansatzes der EU. Abschließend werden Empfehlungen für eine Neuausrichtung der EU-Politik in der Sahelzone gegeben, um Fehler der Vergangenheit zu korrigieren, weiteren Schaden zu verhindern und sich an die sich verändernden Gegebenheiten in der Region anzupassen.

Introduction

Geopolitics are changing fast in the Sahel. Over the past three years, the region, one of the most impoverished and imperilled of the world, has undergone a dramatic cycle of regime change and alliance shift, which has significantly challenged the existing strategy and engagement of the European Union (EU) and its member states in the region. Against the background of this severe crisis in EU-Africa relations and growing anti-Western sentiments, new international players are appearing or increasing their influence, such as Russia, Russia, Turkey or the Gulf States.

It is now urgent for the EU to acknowledge the new situation in the Sahel region and rethink its approach. “The risk of deselection” (Lindskov Jacobsen & Larsen, 2023, 278) is high. If Europe wants to remain engaged in the region, it should forge a new path guided by day-after policies, with a view to rebuilding trust in the EU as a reliable partner.

This Policy Analysis draws on the Panel Discussion held at the oiip’s venue on 28 November 2024 on the same topic, in cooperation with the Austrian Federal Ministry of Defence (bmlv). This event, moderated by two of the co-authors of the present paper, featured the following panellists:

- Robert Zischg, Director, Sub-Sahara Africa & African Union, Austrian Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs.

- Fidelis Etah Ewane, Political Advisor to the EU Special Representative for the Sahel, European External Action Service (EEAS).

- Amandine Gnanguênon, Senior Fellow and Head of the Geopolitics Program at the Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI).

After recalling the developments that led to the termination of the EU’s field missions in the Sahel and the closure and redeployment of many of its member states’ diplomatic representations, this paper addresses a series of questions which were discussed with the panellists: how to avoid that the EU’s efforts are entirely wasted, as the former High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell wondered (Borrell, 2020), but rather contribute towards preventing further destabilisation of the region? How should Europe position itself vis-à-vis the new military regimes? How to react to the new geopolitical dynamics and the growing influence and leverage of other actors in the region? What options does the EU have? It ends up with a series of recommendations about a possible ‘recalibration’ of the EU’s approach in the Sahel.

****

The strategic location between the North African coast and the southern sub-Saharan countries together with its richness in natural resources make the Sahel an area of significant interest to the European Union (EU). Following the escalation of violence after the 2012 rebellion in northern Mali and the coup d’état which ousted President Toumani Touré, the EU became heavily engaged in trying to restore stability, building security and promoting peace in the region. Based on its first Strategy for security and development in the Sahel, reinforced with the EU’s 2015-2020 Regional Action Plan (RAP), the EU deployed three Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions in the area with the main objective to provide long-term security sector reform (SSR). A fourth mission, the military partnership mission in Niger (EUMPM Niger) was launched in December 2022, but the July 2023 coup in Niger prevented its deployment. The 2015 migration crisis further pushed the Sahel to the very top of the EU’s foreign agenda.

The Sahel countries

Source: Samy Chahri, EPRS, In: Ioannides, 2020, Fig. 1, 1.

During more than ten years, the Sahel has been the laboratory of the EU’s integrated ‘train and equip’ approach[1] (Lopez Lucia, 2017; Venturi, 2017). In many regards, the EU’s engagement in the Sahel has contributed to the Union’s attempt to act as a global security actor (Cold-Ravnkilde & Nissen, 2020, 937), based on the 2016 Global Strategy for the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy.

The protracted and widespread crisis that culminated in five military coups d’état in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger between 2020 and 2023 put an unexpected end to this process.

In Mali, the EU’s military Training Mission (EUTM) ended its 11 years presence on 17 May 2024, at the end of its fifth mandate, without having contributed to any significant improvement of the security situation. The July 2023 coup in Niger dealt a final blow to the EU’s strategies and ambitions. In a letter of notification sent on 4 December 2023, the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP) denounced the agreement on the status of the civilian capacity-building mission in Niger (EUCAP Sahel Niger) and withdrew the consent previously granted for the deployment of the EUMPM, giving both missions six months to wind down; a decision that Brussels could only “regret” (Borrell, 2023). This move came only days after the military leaders announced that Niger and Burkina Faso would quit all instances of the G5 Sahel, a regional coordination framework established with European financial, logistical and material support in 2014, following Mali’s previous withdrawal from the alliance. Russian troops soon deployed to Burkina Faso (January 2024), which hailed Russia as its “strategic ally” (Al Jazeera, 2023), and Niger (April 2024) to defend the country’s leader, train national forces and, reportedly, deliver anti-aircraft systems.

The EU’s prolonged endeavours in the Sahel region seem to be eroding, with little to no tangible progress being made. . Of the four EU missions deployed in the Sahel until 2023, the EU is now left only with its civilian capacity-building mission in Mali (EUCAP Sahel Mali) which survives in a precarious and unstable political and diplomatic environment with a mandate extended until 31 January 2025. Building the capacity of military and security forces in the Sahel region has cost more than one billion euros, but have not brought any tangible improvement on the ground. What was once called ‘a lighthouse project’ for the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) (Cold-Ravnkilde & Nissen, 2020, 935) has gone out. The EU also found itself in a rather uncomfortable position, given that part of the military forces involved in the coups had worked with and been trained by the EU or some of its member states, notably France (European Democracy Hub, 2024; Pichon, 2020, 6).

Is this the end of European influence in Africa? Far from the EU’s dream of a ring of friends around Europe, with friendly and stable neighbours stretching from the Caucasus to the Sahara, the Sahel has arguably added its spark to the ring of fire around Europe. Africa’s ‘coup belt’ now stretches from the Red Sea in Sudan to the Atlantic Ocean in Guinea.

Despite facing such a challenging context, Europe cannot turn its back on the Sahel. Given the geographical proximity, the geopolitical and economic importance for Europe as well as the demographic pressure in the Sahel, the EU can neither afford insecurity in the Sahel region nor to fully lose influence. However, the Union now has “to figure out what approach to take in the Sahel with what is currently on the table: […] military governments with ambitions to stay in power, an expanding jihadist threat and an increasingly dire humanitarian situation with record high numbers of displaced persons and food insecurity” (Wilén, 2023, 4). The continuation of the status quo is out of question. There is a need for both an exit strategy on the short term and a reorientation of the EU’s policy and engagement on the longer term. The EU faces a loss in trust and reputation, and the present situation offers an opening for long overdue rethink and repositioning.

The Sahel, a showcase for the loss of Western influence

While France, the former colonial power, had been a key driver behind the EU’s engagement in the Sahel since 2012[2] and was the first to be evicted by the three juntas in a context of growing anti-French sentiments, the broader rejection of Western intervention in the region is affecting other EU member states too. France’s loss of influence has been “a loss for the EU as a whole” (Wilén, 2023, 4). In a context of strong anti-colonial sentiments, Brussels obviously failed to distance itself from the colonial past of some of its member states and (Caruso et al., 2024). The anti-Western tendencies also affect non-EU international actors present in the region, such as the United Kingdom or the United States. The UK announced the withdrawal of its peacekeeping forces from Mali in 2022. On 16 March 2024, Niger abruptly decided to revoke its military cooperation agreement with the U.S. despite Washington’s diplomatic manoeuvres to avoid vacating the premises. The U.S. started the process of removing its approximately 650 troops from the country, where it formerly operated three strategic air bases, including the second-largest U.S. air force base in Africa, a drone base referred to as “Nigerien Air Base 201” in Agadez, northern Niger, only to be replaced by Russian troops (Kola, 2024; Rae Armstrong, 2024).

The regime changes in the Sahel brought to power more assertive governments that are no longer willing to maintain ‘traditional’ partnerships. Instead they are looking for new international partners, interested in filling the vacant position.

By turning away from France, the EU and the West in general, the military juntas that have taken power in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger see Russia as their primary security partner, and this for several reasons. Russia comes without a colonial burden – at least in Africa – which allows Moscow to support and show understanding for local grievances against ex-colonial powers. Security assistance offered by Russia also comes without interference into politics and internal affairs nor any value-based conditions that usually come along with European assistance. Whereas the West either condemned the coups and called for an immediate liberation and restoration of the toppled governments, or at least expressed deep concern over the political developments, Russia is assisting without commenting on domestic developments. Moscow quickly provided military assistance, training and operations to the new regimes through its paramilitary groups, mainly the Wagner group, rebranded ‘Africa corps’ (Czerep & Bryjka, 2024). Moscow demands in return diplomatic support at UN level, mining concessions, and access to the national energy markets (EU Parliament, 2024). For Russia, increasing relationship with African states presents an opportunity to break the diplomatic and economic isolation imposed by the West, strengthen its international position and relevance, and advance geo-strategic ambitions in key areas, such as mining, energy or military presence (EU Parliament, 2024a). Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation, has engaged with Niger’s military-led authorities to discuss acquiring assets owned by France’s Orano SA (Bloomberg, 2024a). In early December 2024, Orano reported that it had "lost operational control" of its mining subsidiary Somaïr of which it owns 63,4%, the rest being owned by the Nigerien state (RFI 2024). The three junta governments have spent the past year trying to renegotiate terms with mining companies to get a bigger share of the revenue, which has also led to arresting mining executives, threatening to revoke permits and seizing mines outright (Lewis, Burton & Crowe 2024). Should Niger halt its exports to Europe completely, the market—already strained by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a consequent 16% reduction in Russian uranium imports — would face even greater pressure. Privileged access to the Central Sahel’s natural resources can provide Russia with significant economic advantages, helping Moscow to sustain its war economy despite the pressure of Western sanctions. Once more, Vladimir Putin pledged Moscow’s “total support” for African countries on 10 November 2024 at a Russia-Africa ministerial conference in Sochi, south-west Russia.

Another attractive partner for Sahel countries is China. Since the end of the 2000s, the People’s Republic is Africa’s largest single trading partner. Over the past 20 years, Beijing has been financing one out of five infrastructure projects on the continent and built one out of three (NBR, 2022). China too avoids any direct involvement in domestic affairs and opts for a much softer approach. Although China’s main interest and motivation lie in ensuring a stable and secure environment for its expanding commercial and economic activities, Beijing is also important for military supplies. The Chinese have been supporting Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger in conducting security and counterterrorism operations and financed the G5 Sahel Joint Force in 2019 in form of aid worth 45.56 million U.S. dollars for security and counterterrorism operations and some 1.5 million U.S. dollars for its permanent secretariat in Nouakchott (Dupuy 2020).

Since the mid-2000’s, also Turkey has become an ever more important actor in Africa. Initially mainly active in humanitarian aid, education and cultural initiatives, the country has progressively broadened its engagement towards the political, military and security levels. With Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, Turkey signed military training cooperation agreements and it is offering comprehensive training programmes (Yaşar, 2022). Most recently, the London-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (OSDH) reported that Turkey was planning to send mercenaries from the private military company Sadat to Niger (Le monde, 7 June 2024). Alongside Russia, Turkey has sent its envoys to secure uranium supplies from Niger (Bloomberg, 2024b).

Last but not least, Iran is seeking to alleviate its international economic and diplomatic isolation by strengthening ties with the ruling juntas in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, who regard the Mullah regime as a potential ally in their anti-Western struggle. Abdoulaye Diop, the Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs, described Iran as a “brotherly and friendly country” and praised it for its “spirit of struggle and courage” (Diop, 2024). Iran is furthermore in negotiations to buy 300 metric tons of uranium ore worth more than $56 million. In exchange, the Mullah regime has promised the Nigerien junta economic aid, agricultural assistance and weapons, including drones and surface-to-air missiles (ADF, 2024).

The region is thus undergoing a strategic reorientation. This shift became clear at the second ‘Russia-Africa: What’s Next?’ youth forum at the Moscow State Institute on International Relations in October 2022, when Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov emphasised: “We are united by the rejection of the so-called ‘rules-based order’ that the former colonial powers are imposing on the world” (radio message quoted by Coakley & Vech, 2022).

A risk of weaponisation of the migration?

Since the so-called migration crisis of 2015, Niger and Mali have become the main transit countries for the majority of people travelling the central Mediterranean route – on a total number of 181,000 migrants and refugees arriving on Italian shores and ports in 2016 – (Bøås, 2021, 57, analyzing Frontex data).

One week before the coup d’état which overthrew President Mohamed Bazoum on 26 July 2023, Niger revoked the 2015 law against "illegal migrant smuggling" adopted as part of an agreement with the EU that criminalized the trafficking of migrants in Niger, and which had resulted in a significant drop of the number of migrants crossing Niger to Libya and Algeria (Weihe, Müller-Funk & Abdou, 2021).“The convictions pronounced pursuant to said law and their effects shall be cancelled,” Niger’s junta leader, General Abdourahmane Tchiani, acted in his decree (Asadu, 2023).

Russia’s expanding influence in the Sahel Zone presents a potential strategic manoeuvre for the Kremlin: the redirection of migration flows towards Europe, following previous instrumentalization at the Russian-Finnish and the Belarussian-Polish borders. Such a strategy would serve to exacerbate the existing migration crisis in Europe, thereby exerting political and social pressure on European governments. This tactic would have to be seen as part of a broader geopolitical strategy to destabilize the EU, leveraging migration as a tool to create internal discord and weaken European cohesion.

Warnings of spillover in the wider region

The crisis in the relations between Europe and Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger in a context of growing anti-western sentiment in Africa and especially West and Central Africa raises the question about potential domino effects in the region. With regard to the growing anti-French movements in countries that used to be Paris’ close partners such as the three Sahelian countries, it makes sense to take a closer look at countries at the Sahel’s periphery with traditionally close relations with France, such as Chad, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. In an area characterized by both an alarming level of terrorism and significantly weak territorial and border control, another question regards the risk of a further broadening of insecurity and instability towards the coastal states of Togo, Ghana and Benin.

Chad

Until very recently, Chad has been considered by the West as one of its last allies in the Sahel region. 1.000 French soldiers have been permanently stationed in the Sahelian country, presenting France’s largest military contingent on the continent. This also explains why Europe has remained discreet in April 2021, when General Mahamat Idriss Déby pre-empted the power following his father’s and former president’s sudden death, and the extremely long transitional period prior to the 2024 elections. France endorsed this undemocratic change of power by putting forward the exceptional circumstances and the necessity to ensure security and stability in the Sahel.

This long-term partnership is however about to come to an end: on 28 November 2024, the Chadian government declared that it is terminating the defence cooperation agreement with France, stating that it is time for the country to assert its full sovereignty and to redefine its strategic partnerships according to national priorities. This declaration was made only a few hours after the 24-hours visit of French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jean-Noël Barrot to the country. It also comes after France had announced a significant reform of its military engagement in Africa, by reducing its military presence on the continent and revising its military cooperation to better respond to its partners’ needs. Whereas this development presents a hard blow not only for France but for the West in general, first signs could already be seen since the beginning of 2024. In January, President Déby was invited to Moscow and met with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. Half a year later, in June 2024, Chad was one of the four countries that Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visited during his African tour. Chad is geopolitically important for Russia, especially with regard to Moscow’s increasing military and economic engagement in the Sahel region and the establishment of a navy base near Port Sudan, on the Red Sea.

Senegal

Senegal, another one of France’s strongest partners in the region, is also considering a reassessment of its relations. On 28 November 2024, the same day that Chad terminated its military cooperation with France, Dakar demanded France to close its military bases in the country, seen as incompatible with Senegal’s national sovereignty. Up to now, about 350 French troops have been stationed in the West African country, making Senegal together with Djibouti, Chad, Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire one of the five last African countries with a permanent French military presence. The 2024 left-wing pan-Africanist president of Senegal, Bassirou Diomaye Faye, has promised a reassessment of the country’s relations with the former colonial power France, but also with the West in general. Soon after his election in April 2024, Faye emphasized that Senegal is open to any partner that is willing to engage in a “virtuous, respectful and mutually productive cooperation”. For the French newspaper Le Monde this “has been a wake-up call for Western countries like France, which are now in competition with many other powers” (cited in Bryant, 2024). In its inaugural speech, President Faye promised “systemic change” in Senegal. During his election campaign, he also put forward the need for Senegal – or West Africa in general – to leave the Franc CFA zone and to create and introduce a new currency, either at the regional (ECOWAS) or at the national level: “There is no real sovereignty without monetary sovereignty” (quoted in Courrier International, 2024). Although so far, no step into this direction has been set, Senegal nevertheless joins Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger in the intention to establish a new monetary system, outside of the French influence zone. After Senegal and the EU have put an end to their fishing agreement in November 2024, claiming both to be the initiator of the non-renewal process, the country’s demand to withdraw the French troops presents another severe turning point.

Côte d’Ivoire

Against the background of these developments in Chad and Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, until recently, could be seen as one of the last French allies in West Africa. Throughout the 2000s, Paris repeatedly intervened in the country’s domestic politics. The government’s close ties with France make the country vulnerable to anti-French movements (ICG, 2023). Moreover, the geographical proximity to Burkina Faso and Mali with which Côte d’Ivoire shares national borders makes it considerably vulnerable to cross-border terrorist activities. This borderland is also a relatively busy trading zone, as roughly 25% of Mali’s and 30-35% of Burkina Faso’s imports come through Côte d’Ivoire. Considerable artisanal gold mining activities attract not only illicit traffickers and smugglers but also armed militant and extremist groups (Eizenga & Gnanguênon, 2024). This tri-border zone has thus seen a significant increase in violent events over the last years (ACLED, 2024). Faced with the threat of instability and the spilling over of violence in the neighbourhood, the government in Abidjan has opted for both military presence in the country’s northern border regions and a series of programmes and measures to promote the population’s access to basic services, strengthen infrastructure, such as paved roads, power lines, schools and clinics, and develop income-generating activities (Eizenga & Gnanguênon, 2024; ICG, 2023).

On 31 December 2024, President of Côte d’Ivoire A. Ouattara officialized a significant downgrade of the French military presence in his country and the retrocession of the French military base of Port-Bouët to the Ivoirian army (Jeannin, 2024). Although this decrease has been coordinated and prepared with France for one and a half year and means no disavow by Côte d’Ivoire nor alliance shift, its coincidence with Chad and Senegal’s recent moves might not have been anticipated by Paris.

Togo, Ghana, and Benin

The threat of cross-border terrorism is also increasingly relevant for Togo, Ghana, and Benin. Jihadi violence spilling over from the Central Sahel into West Africa’s coastal states presents a growing security challenge. Counterinsurgency efforts in Burkina Faso and Niger have pushed Islamist extremist groups southward. They have been able to establish footholds in these coastal countries, exploiting porous borders and limited state presence in northern regions. Despite efforts to coordinate more effectively through the 2017 Accra Initiative aiming to prevent the spillover of terrorism from the Sahel, these countries have only seen limited success in curbing the spread of transnational terrorism. The EU Security and Defence Initiative in support of West African countries of the Gulf of Guinea represents a strategic effort to bolster these states’ counterterrorism capabilities, aiming to curb jihadi safe havens and prevent the further spread of instability. The mission began in late 2023 with an initial duration of two years and a relatively limited mandate to build the capacity of the national security and defence forces and to identify specific needs and develop advisory or training projects with local partners. Ongoing EU support for maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea complements this. In January 2020, the EU launched the Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP) initiative to strengthen its role as a maritime security provider in the Gulf of Guinea. Through the CMP, EU member states aim to enhance operational maritime capabilities by maintaining a sustained and collective naval presence in the region. In reality, however, this routinely translates into the presence of only one vessel. Such limited deployment raises questions about the EU’s ability to project meaningful influence and achieve its maritime security objectives in the region.

The collapse of regional cooperation and its implications for Europe

West Africa has often been presented as exemplary for its regional integration and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) as a trendsetter, especially with regard to security cooperation. On 28 January 2024, however, the military leaders of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger declared their intention to quit ECOWAS with immediate effect. Even if, according to the Community’s statute, any withdrawal requires a one-year transition period, the three states’ exit is a fait accompli that seriously challenges the West African regional cooperation.

After the military takeovers, ECOWAS had suspended the membership of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. The organization also imposed sanctions on Mali and Niger. Following the coup d’état in Niger, ECOWAS even considered the deployment of a Standby Force in order to restore the power of the ousted President Mohamed Bazoum, with the backing of France and the U.S. However, the military intervention did not materialize due to lacking support from the African Union as well as several member states’ opposition. This once more proved the Community’s difficulties in responding to political crises.

On 16 September 2023, prior to their walk out from ECOWAS, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger founded the Alliance of Sahel States/Alliance des Etats du Sahel (AES/ASS), a new mutual defense pact. The new AES/ASS is rearranging the regional landscape. Although ECOWAS promptly replied by lifting all sanctions, the military juntas persist in their decision to quit the regional community and pursue their cooperation within the new AES. This regional disorder – also labelled 'Sahelexit' in the media (EU Parliament, 2024b) – plunged ECOWAS into a deep crisis.

Beyond its direct impact on ECOWAS’ credibility as regional player, as well as on the future of West Africa’s continuous regional integration, Sahelexit is likely to have implications for Europe as well. ECOWAS and the EU look back to a long-lasting relationship that progressively evolved from aid for trade and development to a much broader cooperation in fields such as climate change, humanitarian crises, violent extremism, political instability and migration (EU Parliament, 2024b). The EU has been one of ECOWAS’ most important financial supporters. In October 2023, the two communities signed seven financial agreements in the areas of peace and security, transport, water management, environment, digitalization, health, and education, for a total of €212.5 million (EU Commission, 2023). In return, the EU relies on ECOWAS and its member states as crucial partners for its migration management and curbing irregular migration to the EU through the Sahel and North Africa.

These shifts in the political structure of the region affect its security architecture. By establishing the AES as a new regional security alliance, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger quitted and thereby contributed to the dissolution of the G5 Sahel. The G5 Sahel was founded in February 2014 by Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger as an intergovernmental cooperation framework to coordinate regional efforts in the field of development and security issues in the Sahel region. Financially, logistically and materially, the group was largely backed by the EU, in particular by France and Germany. In May 2022, first Mali quit the alliance after being denied to hold the rotating presidency after two coups d’état. In a joint statement, Burkina Faso and Niger deplored that the G5 Sahel was “failing to achieve its objectives” and “cannot serve foreign interests to the detriments of our people, and even less the dictates of any power in the name of a partnership that treats them like children, denying the sovereignty of our peoples” (RFI, 02/12/2023).

Increasing criticism of the West and in particular France has been accompanied by a pivot to Russia, which has become an important partner for Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, also when it comes to regional cooperation. Instead of the EU and France’s military, material or financial support, the three states’ regional cooperation now relies on Moscow.

What are EU’s alternatives?

The EU made Africa a top priority. It is no coincidence that each of the 2019-2024 EU’s top three leaders with regard to foreign policy – Ursula von der Leyen, Charles Michel and Josep Borrell – travelled to Addis Ababa, where the African Union is based, in the first three months after taking office, but rather a clear sign of the strategic importance of Africa for the EU.

Now that the EU’s engagement in the central Sahel has failed, this priority already seems in jeopardy. Maintaining and simply adjusting the actual EU’s security approach in the region is not possible. The 2021 Integrated Strategy in the Sahel (ISS) could have provided one opportunity for a course correction, but it came too late to bear the expected fruits. The window of opportunity for the ‘strategic reset’ which ISS was advocating for has been closed. The possibility of a “geopolitical New Deal” (Bansept & Tenenbaum, 2022; Moreno-Cosgrove, 2022, 8), whereby Europe would seek to establish balanced relations with the Sahel region, has now been exhausted. The commitment of the countries in the region and their population directly concerned is indispensable (Ioannides, 2020, III); but with the general anger and discontent over the EU’s engagement that brought no real improvement, this will be a tough one that calls for a particular degree of tact and skill. Thus “the status quo as an acceptable outcome”, which Dennis Tull was arguing for – the international community, including the EU, pursuing its current approach even though it is not producing tangible results (Tull, 2019, 420-421) -, is not an option anymore. Redeployment of the common security and defence policy (CSDP) missions, which at some point seemed the panacea, is now hardly practicable. Even worse, their closure led to a loss of negotiating power, country knowledge and social capital, and makes it impossible to follow up on projects already started.

Engaging with anti-Western military regimes under significant Russian influence rightfully does not seem to be a priority for the EU Commission, with Ursula von der Leyen stating that the Union must focus on cooperation with ‘legitimate’ governments and regional organisations (Von der Leyen, 2023). In reality, these noble aspirations tend to favour governments that are open to cooperation with Europe. As the most recent developments in Chad and Senegal however show, Europe is by far no longer a privileged actor in Africa and will have to acknowledge and somehow adjust to the multi-partner approach of most states.

EU initiatives, such as the Global Gateway Initiative (GGI), could offer a good way to follow. The GGI, a strategic €300 billion investment plan targeting major infrastructure projects from 2021 to 2027, represents Europe’s strategic counter to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with €150 billion specifically earmarked for infrastructure projects in Africa. These investments are coupled with the "Team Europe" approach, which seeks to leverage the collective expertise and capacities of various European entities to offer a comprehensive package. A recently leaked briefing for the new European Commissioner for International Partnerships reveals that the "battle of offers" regarding investment partnerships with emerging markets is a major concern for EU leadership (Politico, 2024). While the GGI has faced criticism as a public relations stunt, rebranding already allocated funds, there are reasons to believe it might be a viable competitor to the BRI. Both schemes operate at comparable investment volumes, but GGI primarily offers grants rather than loans. This could provide a competitive edge, as African leaders are increasingly wary of the downsides associated with China’s loan system. Furthermore, although the BRI has been successful partly due to its lack of conditionality mechanisms, the GGI’s value-based investment structure, which adheres to international ecological and labour standards, could enhance the long-term viability of infrastructure investments. This adherence to standards might be perceived as an advantage, promoting sustainable and responsible development.

The Africa-EU partnership, a multi-actor collaboration steered by the EU and African Union (AU) member states alongside non-state actors, civil society organizations, youth bodies, economic and social stakeholders, and the private sector, represents another strategic instrument the EU may leverage to bolster its influence on the African continent. Whereas the Africa-EU partnership holds significant potential due to its inclusive, multi-actor approach which aims at fostering mutual benefits and addressing shared challenges, it has progressively come to a hold over the last years in an increasingly changing global geopolitical environment. Also the EU’s approach to address the continent as one actor has resulted in ignoring the individual states’ specificities and led to both vague and not fully implementable agreements. Against this background, the partnership should be reassessed and recalibrated to be able to effectively reflect and consider the various perspectives, priorities and interests in the two continents.

Are ‘solo’ approaches from some EU members a possible way out?

The military juntas in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are eager to explore new international partnerships, which are seen as having more benevolent intentions (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2024). Against this background, Italy is among the few European countries with continued engagement with the de facto governments of the region. By adopting a pragmatic approach and driven by own interests, the Meloni government has managed to maintain its cooperation with Niger without interruption after the 26 July 2023 coup (ANP, 2024; Audiello, 2024). Through its continued bilateral military training and support mission in Niger (MISIN),[3] Italy remains the only foreign country, apart from Russia, with a military presence in Niger. MISIN was established in 2018 under a bilateral agreement between Niger and Italy. This initiative underscores Italy’s strategic interests in Niger, which serves as a critical transit hub for migration routes toward Southern Europe. Additionally, Italy seeks to address broader security concerns, including the illicit trafficking of goods and the proliferation of jihadist violence in the region (D’Amato 2023).

There are significant concerns about Italy’s unilateral defiance of the EU’s broader agenda. The EU has traditionally operated within a framework of conditionality, rewarding countries in the region for democratic progress and good governance while penalising those that regress, such as Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Italy’s pragmatic stance of non-interference in internal affairs stands in stark contrast to this approach and seems more in line with that of Russia and China, where conditionality is notably absent. For its own strategic gain, Meloni’s government is defying the EU agenda, which has sanctioned members of the Nigerien junta and condemned the coup. This undermines the EU’s pro-democracy stance and compromises the Union’s values. The EU’s apparent acquiescence to this divergence further calls into question the sincerity and effectiveness of its conditionality mechanism.

Ironically, this emerging dynamic could even work to the EU’s advantage. Through Italy’s active engagement, Europe retains a foothold of influence in the region. Financial constraints are forcing Giorgia Meloni to seek multilateral support for her ambitious Mattei Plan for Africa,[4] a detailed mapping of the most strategic projects and initiatives of Italy in Africa, presented in January 2024 and aimed at strengthening Italy’s role on the continent through energy security and economic projects. This diplomatic initiative, “a new approach: non-predatory, non-paternalistic, but also not charitable,” (Klomegah, 2024), received cautious approval from African leaders at the recent Italy-Africa summit in Rome (Darnis, 2024). Interestingly, its objectives are closely aligned with those of the EU’s GGI. Commentators suggest that integrating the Mattei Plan into the GGI framework could alleviate financial constraints and reduce the risks associated with unilateral action (Varvelli, 2024; Simonelli, Fantappiè, & Goretti, 2024). Ursula von der Leyen has already expressed support for this alignment (Von der Leyen, 2024).

Worth being mentioned in this context is also Hungary’s engagement. Budapest has been deepening its bilateral relations with Chad especially since 2023, focusing in particular on cooperation in the military and agricultural sector. In November 2023, the Hungarian government approved a 200-troop military mission to Chad aimed to fortify regional stability through migration management, counterterrorism, and humanitarian support (Servida, 2024). Given the close relationship between Budapest and Moscow and the – in contrast – strained relations between the Hungarian president Victor Orbán and the EU Commission leadership, some observers speak of a “complex diplomatic landscape” in which the mission is going to be implemented. Moreover, they consider that “Hungary will likely encounter opposition from other EU states” (Servida, 2024). This complexity is now further enhanced by the termination of the military agreement between N’Djamena and Paris and the withdrawal of the French troops.

Other European countries recently promoted a "new approach" of fair and mutually beneficial cooperation based on equal footing. In 2023, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development adopted the new ministerial Africa strategy “Shaping the future with Africa” calling for a “partnership based on respect and reciprocity” and “build an open and honest dialogue” (BMZ, 2023). The Danish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Lars Løkke Rasmussens, called in Spring 2024 for “a new approach, not only think[ing] in terms of emergency aid, but much more about cooperation on equal terms” (Rasmussen, 2024). These reorientation attempts might help setting the relations between Europe and Africa on a new ground and allow for greater room for manoeuvre with African countries, whose populations are increasingly aware and critical of neo-colonial practices. However, critics warn that this new approach may just be ‘old wine in new bottles’, as evidenced by the gap between rhetoric and action that marks France’s policy in the Sahel (Saviolo, 2024). Moreover, they might not be enough to respond to the geopolitical dynamics that are currently taking place in West Africa.

Can the EU simply bet on the failure of the three juntas?

Beyond the appearance of public support, the Sahelian military regimes are far from consolidated. In June 2024, reports of heavy gunfire near the presidential palace and inside a military base and the state television headquarters in the Burkinabe capital, Ouagadougou, have spurred rumours of dissent and a potential mutiny within the military (Lawal, 2024). It would not be a surprise if “coups within a coup” (Haidara, 2021) soon resumed in the region.

After a short respite, deadly clashes between government forces, local militias, rebel groups and other violent extremist organizations have resumed in full swing in the Sahel. According to the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP), “The epicentre of terrorism has now conclusively shifted out of the Middle East and into the Central Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa. (…) The increase in terrorism in the Sahel over the past 15 years has been dramatic, with deaths rising 2,860 per cent, and incidents rising 1,266 per cent over this period. Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger account for most of the terrorism deaths in the region.” (IEP, 2024, 3-4). The rejection of Western support by Sahelian juntas facilitates the territorial anchorage of terrorists and the extension of their areas of action towards the Gulf of Guinea, with more victims as a result.

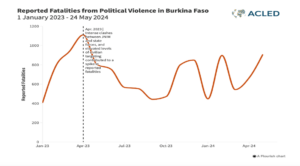

Burkina Faso, a country previously less prone to jihadi attacks, has become a stark symbol of worsening security trends in the Sahel region. The eleventh edition of the global Terrorism Index (GTI) ranked Burkina Faso first on the list of the countries most impacted by terrorism in 2023. After his coup in September 2022, Captain Ibrahim Traoré based his fight against jihadism on the enrolment of civilians alongside military and security forces. This strategy only led to an explosion of violence, with the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Support Group for Islam and Muslims, or JNIM) multiplying attacks against the population as reprisal. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), military forces seem to be the deadliest perpetrator of violence toward civilians (ACLED, 2024b). A Human Rights Watch report said that Burkina Faso’s military executed at least 223 civilians, including 56 children, in February 2024 from two villages whose residents were accused of cooperating with terrorists (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

Source: ACLED 2024b

On 21 October, the NGO Médecins sans Frontières reported leaving the country’s north due to the deteriorating security situation.

In Mali, the arrival of Wagner forces in the country and their involvement alongside the Malian armed forces has drastically increased human rights violations in the centre of the country. Civilian casualties in Mali have risen disproportionately (Mednick, 2023), following clear patterns of the group’s violence against local populations in Central African Republic, Libya, Syria and Ukraine (Stronski, 2023).

The Russian support might yet be running out of steam. After initial “marketing” successes and short-term victories in 2023, the alternative offered by Russia is starting to fail to deliver on promises of security and stability.

On 27 July 2024, rebels from the Permanent Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (CSP-DPA) and militants from JNIM carried out a deadly ambush on a joint Wagner and Malian military convoy near Tin Zaouatene in the Kidal region close to the Algerian border. This ambush resulted in the highest reported number of Russian private military company fatalities on the African continent in a single event since Russia began deploying mercenaries to the continent in 2017 (ACLED, 2024a). In the wake of the ambush, a spokesperson for Ukrainian military intelligence claimed that their forces had provided the rebels with critical information necessary for the operation (Walker, 2024). This assertion highlights the complex web of alliances and hostilities that extend beyond the immediate theatres of war, linking the conflict in Ukraine to other geopolitical flashpoints. Consequently, the governments of Mali and Niger have severed all diplomatic relations with Ukraine, further entrenching their pro-Russian stance. Three months later, at the end of September, Wagner and the Malian forces were forced to abandon their plans to take Tin Zaouatene in retaliation after Algeria warned Moscow of the dangers of the operation (Roger & Bobin, 2024). In October, the media Jeune Afrique asked: “Does the relationship between the Malian forces and Wagner have any future?” (Glez, 2024).

Russia is fighting a major war in Ukraine and might not be able to support the three countries as much as they would require. The ‘Bear brigade’ of Russian mercenaries, who arrived in May 2024 in Burkina Faso to support the Captain Ibrahim Traoré’s regime, left the country at the end of August, officially to contribute to Russia’s war effort in Ukraine but possibly because of internal dissatisfaction among Russian mercenaries (Eydoux & Roger, 2024). This departure happened only days after the bloody Barsalogho massacre on 24 August perpetuated by JNIM, the worst ever experienced by the country with hundreds of victims (Vandoome, Paton Walsh & Mezzofiore, 2024).

Taking shelter under the Russian shield therefore risks being a ‘lose-lose’ option at every turn: the growing dependence and isolation of the countries and their leaders; the loss of budgetary support from the West; the progressive loss of control over their territories; the destruction of institutions by the new Russian colonial logic and then by the military successes of the jihadists, are all consequences that could cost much in comparison with the “insurance policy” offered by Russia (Guiffard, 2022). The rapid fall and escape of Syrian President Bachar al-Assad, the Russians’ protégé, and the regime change in Syria, also showed that Moscow’s protection is never intangible and brought nervosity among the new pro-Russian African leaders (Bobin, Grynszpan & Roger, 2024). In this regard, some observers are arguing that “the best strategy for countering Russian influence may be to draw back and leave Russia with enough rope to hang itself” (Rae Armstrong, 2024).

However, simply waiting for Russia’s failure would be too short-sighted for the EU. The consequences of such failure, like the increase in terrorism and migration, would directly affect Europe. And this is not in the EU’s interest.

The day after: our recommendations

- Navigate between assertiveness and flexibility

As Josep Borrell made it clear, “The European Union intends and hopes to stay engaged in Mali and the Sahel but not at any cost.” (quoted by Fox, 2022). The EU needs “to be coherent, and consistent as well” and “firm in (its) approach”, outgoing EU Special Representative for the Sahel Emanuela Del Re also stated (Welsh, 2022). It should avoid compromising about its core values.

Such an approach should however leave enough room for flexibility and adaptability to the changing and complex situation if the EU wants to rebuild trust, restore a positive image and re-establish itself as a reliable partner. “The only winning strategy is dialogue”, as only dialogue is “capable of protecting the interests of the EU and preparing it for future changes”, E. Del Re recognized during her visit to Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso and Chad in November 2024. Although she stressed that this conviction is in line with that of “the United Nations and other important actors, such as the World Bank”, it goes against the approaches favoured by other EU member countries, in particular France. But “even going against the grain, […] this is the only strategy”, she said (Nova.news, 2024).

Ignoring or penalizing the juntas and entering into a logic of competition with Moscow and other external actors is hardly an option. In an increasingly evolving global order, with transitional authorities and further escalation of tensions, pressure instead of diplomacy risks having an even more adverse impact. In the Sahel, the experience with the recent series of coups shows that a hardline stance based on the imposition of sanctions leads to worse conditions for the population, accrued influence of rival powers, rising nationalism, and increased violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. These only benefit extremist groups by expanding their territorial control and fuelling radicalization (Marangio, 2024, 5-7). Moreover, the change of power in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger differ to most other military coups in Africa in so far as the military governments are supported by the local populations. Sanctioning them would thus go against the public opinion and neglect local positions and concerns.

- More country-focused approach

As the Panel Discussion on 28th November 2024 highlighted, the ‘one size fits all’ approach has not worked. The EU should now privilege a ‘country by country’ approach by tailoring to each context. Local dynamics should be better taken into consideration, as well as the ‘social contract’ involving various stakeholder groups (civil society organisations, local militias or rebel groups). If Europe wants to remain engaged in the Sahel, it needs to be clear about what it can offer, what added value it brings compared to other international actors, and what own interests it pursues while responding to the various and specific interests, expectations and demands on the ground.

- Question capacity-building as ‘strategic stubbornness’

The EU’s capacity-building ‘obsession’ should be questioned. Applied to administratively weak and politically fragile states and disconnected local governance, it has led to an impasse and turned to “foreign policy entrapment” rendering possible alternatives implausible (Plank & Bergmann, 2021). Early warning signals have been ignored.

- More transparency and consistency

Central to the reproach made by EU’s partners is that for too long, Europe has not been clear and transparent enough about the economic, geopolitical and strategic interests behind its engagement and instead has hidden them behind a value-based approach. The EU’s inconsistent reaction to unconstitutional changes of government in West and Central Africa, depending on the country’s alignment with the West, has been a case in point. While condemning the coups in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, the EU kept a low profile after the undemocratic change of power in Chad in April 2021 and the coup in Gabon in August 2023. This diverging approach and lack of any cohesive and coherent strategy led to accusations of applying double standards, driven by own – partly hidden – interests, which further fuelled the deterioration of the relations between the EU and several African states (Caruso et al., 2024). Even if this frustration is only one element of the current crisis, the African partners definitely request more transparency, and a partnership built on a constant dialogue and exchange of positions.

- Rely more on individual member states’ capacities and specificities

EU’s mistake has also been to ‘hide’ behind major post-colonial players in the region, mainly France. In the future, the EU would gain in better channelling the specificities of its different member states, aligning national interests and building a real synthesis of them.

- Fight the battle of narratives

Attempts to further discredit the EU in the Sahel and fuel anti-Western rhetoric are likely to intensify in an effort to make geopolitical gains or widen the gap between Europe and Africa (Faleg & Palleschi, 2020, 2 & 80).

It is certainly quite late for communicating openly with Sahelian populations. But the EU must nevertheless invest in strategic and targeted communication to set the dialogue on a new level, create space for exchanges and improve its image in the region. A particularly important group is the younger generation, well represented among the putschists – Captain Ibrahim Traoré, Burkina’s interim president, is 37 years old – who in particular wants to break with traditional partnerships and is blaming France and the West for their neo-colonial behaviour. Communication should thus aim at promoting a positive image of Europe as a reliable partner while unveiling misinformation and setting things right in order.

- Diplomatic messaging from the international community needs to be consistent

Although both have interests in the Sahel region, the United States and the EU should avoid undercutting each other, especially when it comes to responding to democratic backsliding. While patronising for unity, Washington is prone to set division between EU countries (Devermont, 2021, 6-7) and advocate for its own interests. Niger’s coup in July 2023, for instance, resulted in a divided response, with French military collaboration being terminated by the new authorities, while U.S. troops tried to remain in Niger without much care for the change of regime by force, before eventually being driven out of the country too. It remains to be seen how the U.S.’s interest in supporting Sahel peace and security operations might develop under the new Trump administration.

- Prevent the spillover of instability from the Sahel to the Gulf of Guinea and to the Mediterranean, without repeating the same mistakes

The EU must support coastal West African countries in keeping the jihadis out and no longer allowing them to use their territories as a safe haven to recover and restock.

However, Brussels should refrain from merely replicating its failed counter-terror-led engagement to West-African coastal states (Guiffard, 2023; Phillips, 2024; Rae Armstrong, 2024). Border security should be the focus, as one of the panellists on 28.11 recommended. Against the background of the developments in the Sahel and the crisis in the relations between the West and Sahel countries, the EU has nevertheless to make sure to effectively reassess its engagement in the Gulf of Guinea. The 2023 launched EU Security and Defence Initiative in the Gulf of Guinea is likely to play a key role here.

- Promote diplomatic coordination with ECOWAS

West Africa is also in a deep regional crisis as ECOWAS’ credibility and strength have significantly suffered from losing Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger as members and the organisation’s failure to adequately and effectively react to it. ECOWAS however remains an important actor and partner for the EU, especially at the economic and security level as well as with regard to migration. ECOWAS is also one of the AU’s regional pillars and contributes to the AU’s Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). The EU and its member states should therefore continue supporting the West African regional community as one of its long-term partners as well as with regard to the Organisation’s central role in promoting the region’s economic development. At the same time, the EU should not ignore that ECOWAS has been heavily fragilized and weakened by the recent events, and especially the drop out of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. As new regional agreements and constellations are being made, the EU has also to analyse these developments and remain open to these dynamics of the regional landscape.

- Stabilize Libya

Insecurity in North Africa must be addressed as a prerequisite for peace in the Sahel region. In particular, the Islamist destabilization of the Sahel region can directly be linked to the violent overthrow of the Libyan regime in 2011 in the context of the Arab Spring and the spread of armed groups and violent extremist organisations, in a context of loosely controlled borders. Therefore, and even if the Sahel’s security has since acquired a logic of its own, the stabilization of Libya, a vital part of the North African landscape and in the Sahel context, is essential for the whole region’s stability.

- How can Austria contribute?

Austria belongs to the group of EU member states which do not give sub-Saharan Africa strategic priority over other geographic areas. However, it actively engages and is expanding its presence in this region (Faleg & Palleschi, 2020, 12). Vienna upgraded its engagement in the last few years, by issuing a new national strategic framework (Austrian Directorate General for Development Cooperation, 2020), opening a new embassy in Ghana and scaling up its activities. In the Sahel, the Austrian Bundesheer was involved in the EUTM Mali mission, which has been led since 2022 by the Austrian Brigadier General Christian Riener. In September 2024, the Austrian Minister of European and Foreign Affairs, Alexander Schallenberg, mentioned the focus on Africa as one of the three challenges for the years to come (BMEIA, 2024).

In a context in which the EU is to analyse, re-think and re-position its engagement, Austria may play a certain role. Without colonial past, it is also one of the few neutral countries in the EU which might ease the re-establishment of contacts with the distrustful Sahel regimes and contribute towards re-establishing confidence. For Austria, stability in the Sahel remains important for reducing the migration pressure and threat of terrorism. Finally, international engagement such as in the current Sahel crisis context can help Austria to confirm itself as a reliable international partner.

However, the panellists on 28.11 recommended Austria not to rush. Vienna should act pragmatically, first understand the new ‘ecosystem’ in the region, and draw on the lessons learned. As emphasized by one panellist on 28.11, ‘strategic patience’ should be the motto.

[1] Based on the German concept of ‘Enable and Enhance’, the formula ‘train and equip’ corresponds to providing equipment to partner countries and international organizations so as to enhance their own performance (see Tardy, 2015, 2).

[2] France intervened in Mali in January 2013, at the request of the Mali government, with Operation Serval to block the advance of jihadists and Tuareg rebels towards the capital Bamako. Serval was followed in August 2014 by Operation Barkhane that had up to 5,500 French soldiers deployed in Mali, Niger and Chad. When France withdrew Barkhane in 2022, it had become the longest French overseas military operation since the end of the Algerian war. Finally, the Takuba Task Force, a European military task force established between 2020 and 2022 to advise and assist the Mali Armed Forces, also operated under French command.

[3] Missione bilaterale di supporto nella Repubblica del Niger – MISIN is a civil-military mission aimed at capacity building of Nigerien forces, surveillance and control of territory as well as combatting illicit traffic and illegal immigration. Through this framework, there are currently around 600 Italian soldiers stationed in Niger.

[4] The Mattei Plan, proposed by Giorgia Meloni, is a strategy aimed at strengthening Italy’s ties with African countries by focusing on energy partnerships, particularly in natural gas, and addressing issues like migration and security. It seeks to create long-term agreements that provide Italy with access to African energy resources while supporting African nations with infrastructure, development aid, and better governance to reduce migration pressures and instability.

Downloads